Rivalries

by Scott Thomas Anderson

Sierra Lodestar

Gold Country newsrooms were boiler plates of emotion during the Civil War

Gold. Men rode for it, dug for it, panned for it, gamed for it and killed for it. In the breakneck fever of 1849, a precious glitter beneath the ground created new camps, buckling fortunes and a whole lot of something else: Havoc. When the dust lifted from a crazed and sometimes bloody decade, the California Mother Lode made way for a new era of civility. However, for some men who crossed paths in towns and ranches, the unbridled energy of the hills never diminished, nor lost its spell, nor stopped pushing them to edge – and never stopped sparking rivalries.

William Penry

The War of Words and Ashes

In 1861, Amador County was far away from the battles of the American Civil War; but mighty pens clashed over the tragic struggle nonetheless, as the area’s two newspapers fought for the permanent soul of the community. It was a confrontation in which printed words were sharper than cavalry sabers and ink ran in the spirit of blood.

It started with a shot fired at Fort Sumter, S.C. Following the events of the war from the boomtown of Jackson was William McMullen, the publisher of the Amador Dispatch. McMullen felt so patriotic about Abraham Lincoln’s cause that he saddled up his horse, joined the Union Army and rode off to be part of the long, epic clash. Given McMullen’s loyalty, some found it curious that the men he left in charge of the Dispatch were George Payne of Virginia and William Penry of Mississippi. Readers would soon discover that both men were fiercely allied with their Southern friends and families. Penry and Payne were among thousands who were still bitter that California had not been made a slave state when it came into the Union. Such rage-criers were known throughout the gold country as Copperheads. Penry eventually hired a new editor; a slave-hating firebrand from Mississippi named L.P. Hall. The three men created a Johnny Reb triad – and the Dispatch was transformed into an unapologetic rallying point for Confederate sympathizers.

In one editorial, the Dispatch described President Lincoln as “a self-confessed perjurer,” a “buffoon,” a “vulgar joker” a “spiritualist” and, worst of all in the minds of Penry and Hall, “an abolitionist” who believed blacks were the white man’s equal.

Today such words cause such rage that it staggers the mind to think a local newspaper ever published them; but even in the 1860s, Amador County had another news agency that was equally offended; the Amador Ledger was as supportive of Lincoln and a Northern victory as the Dispatch was of slavery and Southern insurrection. The Ledger’s publisher, Tom Springer, wasted no time in attacking his ink-smudged rivals. Springer wrote columns that took personal aim at the men steering the Dispatch. He referred to Penry as a rather “unsophisticated young man,” before announcing to readers that Hall was a shifty propagandist who “palms off his copperhead balderdash as the productions of the simpletons who ostensibly own the concern.”

The dirt-stained roughnecks of Calaveras County had a profound

impact on both Mark Twain and Bret Hart.

The men at the Dispatch didn’t take the insults lying down. They quickly fired back columns declaring that the Ledger “spreads abolitionist filth on white paper,” adding that it was written “by pap-sucking scribblers.”

The two newspapers continued to fling mud at one another right up until Lincoln’s assassination on April 15, 1865. When the Derringer came out in Ford’s Theatre that night, thousands of Amadorians – particularly those who worked at the Ledger – were devastated by the loss of their commander in chief. And Amador had been on Lincoln’s mind, too. As historian Larry Cenotto points out in his book “Logan’s Alley Volume I,” one of the last tasks the Great Emancipator performed before his slaying was authorizing a squad of Union cavalry to ride into the city of Ione to clear squatters from a new land grant. The arrival of those blue-clad soldiers would play an ironic role in the dead president getting revenge on the Amador Dispatch.

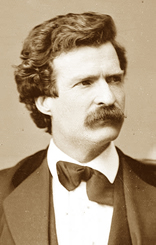

Mark Twain

On April 29, 1865, the Dispatch published a lengthy column that, in the words of Cenotto, “… celebrated Lincoln’s death and made it clear that the newspaper felt he’d gotten what he deserved.” The Ledger must have fired off a scathing response; but no amount of published words could sting Penry and Hall the way Destiny saw fit when their shocking statements reached the Union cavalry men who were still camped outside of Ione.

As the sun broke over Jackson’s main street on May 8, 1865, Penry and Hall were pulled out of their beds at gunpoint, arrested by Union forces and made to watch as the doors of the Amador Dispatch were chained shut. Fuming, the cavalry marched Penry and Hall on foot all the way from Amador County to San Francisco, locking them up in the relatively new military prison, Alcatraz Island. Accounts from Penry and Hall confirm the two were literally shackled to balls and chains and fed crumbs and water. Meanwhile, an angry mob looted and burned the office of the Amador Dispatch, leaving a smoldering pile of ash for all Copperheads to remember.

“It’s a story that really tells us how the Civil War affected this remote state in the U.S,” Cenotto reflected. “It tells us that in war, the authority takes away and restores liberties in its own good time. It tells us how one small county could be riven by political differences and animosities which, in time, were overcome if not forgotten.”

Six weeks after their arrest, Penry and Hall were released from Alcatraz on the humiliating condition of taking an oath of allegiance to the United States. Surprisingly, Penry spent the rest of his years in Amador County. The Amador Dispatch and the Amador Ledger continued to experience a palpable tension for the next 125 years – until the McClatchy Co. merged the two publications into one unified newspaper in the 1990s as the Amador Ledger Dispatch.

A Tale of Two Writers – at Each Other’s Throats

Bret Harte

One would sell the Western dream to the East, bringing the genre of “regional writing” to the greatest heights it ever saw before he faded into labels, poor fortunes and academic obscurity. The other would dawn a crass, cagey voice and half-smoked cigar as he bragged about youthful vandals and whispering rivers. In doing so, he would breed a literary rock star for the ages – an icon whose silver hair and savage wit are permanently embedded in the American psyche.

Bret Harte and Samuel Clemens each won his first taste of national fame by writing about Calaveras County. The dual breakthrough forged a volatile friendship between the young men, a friendship that would eventually crumble into the bitterest of personal rivalries.

Harte and Clemens met in 1864, when Harte was an editor at the Californian in San Francisco and Clemens was a poorly paid contributor. Hesitant from the outset, Clemens viewed his new boss as prim and fatally snobby. However, there could be no doubt with the foul-mouthed, disheveled contributor – or with anyone for that matter – that Harte was the first wandering poet of the Gold Rush, deeply embedded in the dirt, desperation and chaos of the frontier.

Harte departed from Oakland at the age of 19, riding into the guts of the unbroken territories. Much of his time was spent in the dusty, isolated creek civilizations between San Andres and Angels Camp. Though often accused of looking down on roughneck prospectors, Harte’s courage as a man and as a journalist was never in doubt. He rode shotgun for Wells Fargo Co. stagecoaches during the heyday of the highwaymen. When he was given a job as a reporter in Humboldt County in 1860, he dared to write truthfully about the gruesome slaughter of 60 Native Americans in Eureka by an angry white mob. Harte made it clear that the bulk of the causalities were women and children. Such an article had never been published in the Gold Country and it earned its author numerous death threats.

Once Clemens took full stock of Harte’s adventures, he decided on friendship. Besides, Clemens had his own problems to worry about. As a writer, he lacked an identity. He loathed convention, and the bland literary standards of the day were strangling his energy and optimism. Salvation came from a friend smashing a glass pitcher over a San Francisco bartender’s head. Fearing the law, Clemens and his pal ran for it. He drifted on to Calaveras County. Then, while patrolling the grungy mining hamlets near Jackass Hill in Tuolumne County, Clemens heard a whopper of a tale about a corrupt frog race. Suddenly he had a radical idea about how to bring the story to life.

For decent society, California was the end of the world, but the rhythms of its rough second-class culture were creeping into Clemens’s voice. His isolation had galvanized him. He’d survived the dim card rooms of Sacramento and the muddy slopes of Angels Camp on his own terms, and now he’d approach the craft of storytelling in a similar way. Years of resentment festered as he carefully lined his victims against the wall: the highbrow language, the trustworthy narrator, the dignified subject matter. These were the first casualties in Clemens’ new war on American style. When he finished “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” he had happily ignored every codified rule of writing. Odd and irreverent, the story made a deadpan mockery of pretension and a virtue of pointlessness.

Even with Clemens’ new story leaping like a Calaveras jumping frog across the country, it was Harte who catapulted to national fame first with his book “The Luck of Roaring Camp,” which offered stories based on his time spent in Calaveras County and other nooks of the Mother Lode. Harte was suddenly a celebrity – and Clemens, who would soon be writing under the name Mark Twain was, for the moment, eclipsed entirely by Harte’s shadow. Wounds began to fester, especially when Harte tried to give Clemens advice on how to author a popular piece of literature.

Yet Clemens would not have to stew in envy for long. The tables dramatically turned when Clemens’ own book about Western romanticism, “Roughing It,” made him the most famous writer in America overnight. Meanwhile, Harte began pumping out one commercial failure after another.

Realizing the authors were no longer equals in the eyes of American readers, Harte begged Clemens to co-write a play with him in 1887. It was a stunt that Harte dreamed might propel him back into a winning streak. Not surprisingly, the two began to argue about creative differences over the play called “Ah Sin.” And then, disaster. On a visit to the Clemens house, Harte’s infamous snobbery got the best of him, as he evidently took a verbal shot at Clemens’ wife, Livy. The two men launched into numerous arguments, culminating in Clemens publicly mocking an absent Harte on the opening night of their doomed play. Clemens and Harte never spoke again.

In his stunning biography, “Mark Twain: A Life,” author Ron Powers writes that Clemens “remained actively and permanently vengeful” toward Harte. To make his case, Powers quotes a letter Clemens wrote upon hearing that Harte was appointed as a U.S. diplomat. Clemens tore his pen out and raged: “Harte is a liar, a thief, a swindler, a snob, a sponge, a coward, a Jeremy Diddler [*cheap skate]. He is brim full of treachery … to send this nasty creature to puke upon the American name in a foreign land is too much!”

Harte died in 1902, an obscure figure living in near destitution. Clemens died eight years later, with few positive things to say about the world and everything in it, particularly Bret Harte.

How a Tuolumne boy saved Berkeley

The Stockton Insane Asylum

Green, sparkling bubbles in flasks. The oil of earthworms stored in crystal Erlenmeyers. Bottles of laudanum and bowls of black leeches. Opium solutions hidden behind the counter for “chasing the dragon.” These were the items a boy from Sonora was surrounded by after coming into the world – a boy who would grow up to combat a major disaster and help shape the future of a city.

In 1864, new gold camps were still springing up in Tuolumne County. The Sonora-Mono Toll Road had just been completed. Ranches were fixed and running; farms were going strong. Watersheds from the mountains above, coupled with a new determination in the community, had sparked a flurry of growing trade. In Sonora, prospectors needed a clever druggist to help cure their ailments. That man was Frederick Spears, who ran a typically strange 19th century pharmacy.

It is well documented that Gold Country druggists of that era often prescribed bizarre concoctions to the suffering faces that walked through their doors. However, Spears may have been relatively more legitimate. He seems to have earned himself a certain amount of prestige throughout the town that was widely known as “The Queen of the Southern Mines.”

When Spears’ son, Charles, was born that year, most people in Sonora would have known about it. Charles spent his early years amidst the hard, fledgling world of Tuolumne society. By the time he was making his way through grammar school, his ever-ambitious father had accepted a new job as the druggist for the Stockton Insane Asylum.

As a young man, Charles Spears would hear the panicked screams at night, echoing down the asylum’s hallways, ringing and whaling against the grand windows, the vaulted arches, the lone Gothic steeple. He would smell the sinister filth of patients creeping through the massive stone hallways. He would see the straight jackets tightened, and the skull restraints buckled, and the flat, coffin-like bars of the Utica cribs shut across mad, desperate faces. It was an inverted world from that of his former Tuolumne home. Though Spears was very young during his time in Sonora, family memories and conversations left him with a vivid image of life on the Mother Lode frontier. They offered a sense of rugged self-identity. The new images Spears was exposed to at the asylum – morbid and mind-bending though they were – forged an ironclad belief in his own intellectual strength. It’s very likely these two universes from Spears’ past built the characteristics that allowed him to become a hero during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. While California fault lines were obliterating the city, Spears – acting as a harbor commissioner – mustered Herculean rescue and reconstruction efforts to help prevent the disaster from bringing San Francisco to its knees.

By the turn of the century, Spears was moving up the ranks of Bay Area politics. He was appointed the port warden of San Francisco and then, in short succession after his heroics, chairman of the state Republican campaign committee. In 1909, he set his sights on becoming the first mayor of Berkeley.

Charles Spears

But Spears had a formidable opponent. Beverly L. Hodgehead was a Renaissance man; a generous patron of music and the arts, a brilliant lawyer who had argued cases before the Supreme Court and a future president of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. He was a figure of style and refinement. In comparison, some in Berkeley viewed Spears to have come from a rustic backwater – Tuolumne being little known and even less thought of – with a father who worked in quack pseudo science.

As the election approached, an old-fashioned, mud-slinging political rivalry erupted between Spears and Hodgehead. To his utter disappointment, Spears was defeated on Election Day. Yet Mayor Hodgehead soon had a new problem on his hands; a dirty political wheel was slowly spinning against the residents of Berkeley, bringing them closer and closer to being absorbed by the city of Oakland. By 1910, the power structure of west Berkeley, along with the backroom, cigar smokers of Oakland, had managed to push through a ballot initiative for total annexation of the entire city to Oakland’s authority.

As Daniella Thompson of the Berkeley Daily Planet pointed out in 2007, Hodgehead was at a disadvantage in fighting off the political maneuver. In 1910, Berkeley had fewer than 6,000 registered voters. Despite Hodgehead’s popularity, he knew he might not be able to save the city without a good number of votes from those who had supported his archrival, Spears, a hero of the San Francisco earthquake. The two combatants reluctantly joined forces. Spears came out before journalists and theatrically declared that he “did not wish to see the pure, ideal government of Berkeley swallowed up in the Babylonian wickedness of Oakland.”

The pairing of a Tuolumne-born maverick and a spokesman for Berkeley’s elite proved potent enough to convince voters, and the Oakland power brokers would never again make an attempt to take over the city.

It’s unknown whether Spears ever returned to visit Tuolumne County before he died in 1928.

William Penry and Tom Springer were newspaper publishers who saw the world in blue and gray. And yet, both men were so in love with the California Gold Country that they staked their reputations, their fortunes and, in Penry’s case, his very freedom, on a grand belief in its future. Samuel Clemens and Bret Harte were American writers of the first order – but neither would be known today had they not battled through what Clemens later remembered as “the land of gold, whiskey, fights and fandangos.” Charles Spears left the Mother Lode when he was young, but he carried its weird gusto with him through trials and challenges that few can imagine. As a poet who died early in the 19th century reflected, all were manifestations of “the spirit of the age.” More importantly, all were manifestations of a more hardened and rugged spirit – the spirit of the Gold County. The spirit of the hills.