Louisiana's Swamps, Rivers and Storm Survivors

by Scott Thomas Anderson

The Press Tribune

The Mississippi flows through America’s oldest tribal memories – a splashing body of jeweled hickory that rolls long and lonely down the continent. The word means “Father of the Waters,” and from the earliest chiefs chanting on its banks to the South’s blood-soaked insurrection, this unstoppable river has been the nation’s widest artery of myth and dreams. But the Mississippi is changing, and changing in ways that affect the rare cultures that have been birthed and re-birthed in its shadow.

Changing rhythms of life on the Mississippi

When Mark Twain penned “Life on the Mississippi” in 1883 he knew the waterscape of his youth was altering forever. The stretch of the Mississippi Twain loved best is the one that’s easiest for modern travelers to experience – the 80 miles of water coiling from Baton Rouge, past New Orleans to the breadth of the Gulf. For most of the 19th century it was a spacious river-run tumbling along flower-laced avenues in Baton Rouge, then lapping between shores of cane fields, pillared mansions and oak trees tasseled in Spanish moss. Those views today have largely been replaced by the rust of oil refineries, sugar factories and massive industrial docks. It takes some historic imagination to see this part of Mississippi’s banks as they once were; though the crew of the Creole Queen riverboat is ready to help visitors find those lost pictures.

The Creole Queen’s dining house has the feel of an antique floating saloon, with its bartenders stirring cocktails and his chefs dishing out gumbo, jambalaya, seafood pasta, and red beans and rice. When the paddleboat pulls away from the Crescent City’s skyline, travelers are in the hands of Charles Chestnutt, a New Orleans-born guide who walked away from a career as a corporate lawyer to be a story-teller on the Gulf. For seven miles the Creole Queen sweeps over the murky glass of the Mississippi on a passage Twain always remembered as “a pilot’s paradise.” Chestnutt takes visitors through 298 years of regional history, from French exploration and to Spanish occupation, to the survival of some of the nation’s first free black communities. The way in which these groups merged – body, food, music and mind – into the complex Creole identity is a phenomenon that takes a lot of explanation.

“Probably the biggest thing to emphasize to visitors is that French influence,” Chestnutt notes. “That French love of life just makes for a slower pace out here. It’s about French sensibilities, Napoleonic law, Spanish architecture, and how all of that evolved in the natural, geographic isolation in this part of the Gulf.”

Arriving at Chalmette’s dock, travelers see a surviving plantation house dropped in a shady vision of oaks bowing under bibs of torn moss. It’s a genuine view from the time Twain was a riverboat pilot. It’s also the preserved battlefield where, on January 8, 1815, Andrew Jackson and a force of American troops, volunteer citizens, backwoods riflemen, Creole privateers, Choctaw Indians and free blacks defeated a British expeditionary force more than twice its size, killing some 2,000 English and Scottish soldiers in less than 30 minutes.

The bloodshed at Chalmette was not the only moment of thunderstruck suffering to hit these grassy fields: The battleground lies just one mile east of New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward.

The Lower Ninth Ward was once an expanse of Cypress swamps and saltwater marshes off the east bank of the Mississippi. In the 1920s drainage canals morphed the bayou into a residential neighborhood at the very moment New Orleans was transitioning from the most diverse cultural melting pot in the South to yet another punishing bastion of institutionalized racism. Black working class families built homes in the Lower Ninth to find as much freedom as they could to protect their heritage; but New Orleans kept developing its Gulf commerce capabilities, and within a few years the ward was geographically pinched between the Mississippi River and an industrial canal sweeping into Lake Pontchartrain – a canal shored up by man-made levies.

As the Creole Queen pulls away from Chalmette’s river dock, Chestnutt points off the bow to the Lower Ninth Ward, taking his passengers day-by-day, hour-by-hour, through the numbing tragedy that changed a nation. It was the moment the world saw that 20,000 American citizens could be abandoned in a blistering hot stadium filled with open sewage and the bodies of their dead family members; and then left that way for five entire days. It was the moment the country learned dozens of its desperate, starving people could try to cross the Mississippi on an iconic bridge only to be turned back at gunpoint by deputies from a wealthier neighborhood. It was the moment one of the most culturally unique cities on the globe was 80-percent under water, and the only rescue parties braving the flood were fisherman rather than the federal government. It was a moment that will forever be known as “when Katrina hit.”

The Creole Queen’s paddlewheel buzzes into the waves and Chestnutt looks out at the empty husk of Holy Cross School on the shoreline. A decade after the hurricane, the 137-year-old community landmark is still covered in blue tarps nailed to its roof. In the years after Katrina hundreds of roofs across the Ninth Ward were covered in these federally-issued tarps. For Chestnutt, whose aunt and uncle survived the deluge, the shiny patches stretched across Holy Cross School trigger memories of his own days volunteering to tear down houses in the storm-devoured neighborhood. Now, with the riverboat cutting over soupy, brown southern waters, Chestnutt can at least tell his group that they’re looking at the last remaining FEMA tarp on a roof in the city.

“I know I’m doing a good job talking about Katrina when I see people crying,” Chestnutt reflects. “Hearing what happened is supposed to be an emotional rollercoaster. It’s a descent into how bad things got in the next five days. And when my listeners are at the bottom of that pit, that’s when I use the poem ‘Invictus.’ I’ve tried different ways of telling the story, but there’s no better way than poetry.”

Holy Cross School is one mile from the house of man whose life’s mission has been preserving the Lower Ninth Ward’s unbreakable culture. Ronald W. Lewis was born and raised on these streets, which happen to be part of the most untamed, energetic parade territory in the world. He was raised around the Lower Ninth’s Social Aide and Pleasure Clubs, community-based support groups that regularly march on special occasions in chic, zoot-suited regalia. The dapper sashes and splashy Boutonnieres donned by these men are emblems of the traditional jazz funeral. Lewis is also connected to the ward’s Skull and Bones gangs, which locals describe as tricksters who haunt Carnival Time dressed in macabre, bone-faced reminders of how African’s animism arrived here through slavery in the Caribbean. More than anything, Lewis grew up with an ongoing tie to the neighborhood’s most impenetrable subculture, the Mardi Gras Indians. Until recently, few outside of New Orleans knew these rhythmic dance groups have existed for 140 years in the drained bayous of the Ninth Ward and the city’s “back of town,” the Treme. Genuine Mardi Gras Indians are an entrancing spectacle: Their handmade costumes – emblazoned with wild, beaded mosaics, high royal headdresses and fountains of windswept feathers – are the black community’s homage to their forefathers’ bond with the Choctaw, as well as a tribute to the renegade spirit of resistance shown by the plains Indians who battled government oppression.

Raised in the Ninth Ward, Lewis has “masked Indian,” though he ultimately became so enamored with the creativity of each tribe that he morphed into a kind of emissary between them: The Creole Wild West; the Yellow Pocahontas; the Wild Magnolias; the Ninth Ward Hunters; the Guardians of the Flame – Ronald Lewis knows them all. When Lewis retired from the New Orleans transit authority in 2002, he began to turn the backyard of his home into a requiem of his neighborhood’s legacy called The House of Dance and Feathers. Soon the city’s social aide & pleasure clubs, skull and bones gangs and Mardi Gras Indians were all donating artistic creations to his mission.

And then came Katrina; and the levees around the Lower Nine Ward failed.

Lewis and his wife managed to escape during the evacuations; but 120,000 residents of New Orleans had no ability to leave. Hundreds in the Ninth Ward died. Lewis came back to find his own house and museum under 14-feet of water. One of his friends discovered an oil tanker from the rail line lying in her backyard. Houses were crushed and crumpled like tissues of broken wood in every direction. It took Lewis two full years just to move back into his residence, and rebuilding the House of Dance and Feathers has been an ongoing obsession ever since.

And so the Ninth Ward has life again, though Lewis, a longtime union man, knows its poverty and struggle are tied to the changing face of the Mississippi River beyond the power of hurricanes: In the 1970s more than 8,000 men from New Orleans worked in the city’s port, which infused livable wages into black and white neighborhoods alike along the riverfront. New Orleans still has the fifth largest port in the nation, but advanced automated cargo systems have rendered many of those jobs as vanished as the Creole pirate empire once hidden in the swamps of Barataria Bay.

“It hard these days,” Lewis reflects. “It used to be that most people here in Ninth worked in the port. We were dock workers. We were longshoremen. We were stevedores. Now there’s a lot less jobs on the river, and people here have to work in the service industry; you know, work in hotels and restaurants. It’s not bad work, but those jobs don’t really pay enough to make it.”

But the Ninth Ward itself “made it through those muddy waters,” as one of its songs says; and it will keep trying to make it through whatever waters are ahead. People like Lewis also know that the social aide and pleasure clubs keep marching with their tuxedoes and batons, and the skull and bone gangs keep lurking on Saint Joseph’s Day, and the Mardi Gras Indians keep dancing down the alleys with their sacred prayer: “No we won’t bow down, on nobody’s ground.”

For the moment, the rhythms of the Lower Ninth Ward do indeed play on.

“The Indians are about keeping a distinct culture alive that’s been going on continuously since the 1800s,” Lewis says. “Now, the kids in the neighborhood are getting excited about it. They want to be part of something bigger. So, I think the culture is going to keep going.”

From St. Jefferson’s swamps to St. James reflectionsIt’s hard for visitors to get away from New Orleans: There’s little to rival wandering under its gray skies and warm rain, passing the baluster-riddled balconies of Dauphine Street, the tropic yards of the Garden District or the rotting, spectral beauty of its above-ground cemeteries – those clustered, vine-touched crypts enclosed like little walled cities of stone. But Louisiana’s charm extends far beyond the heart of the Big Easy. Its cultural chemistry is just as alive in the swamp-side neighborhoods of Jefferson Parish or the haunting “plantation lands” of Saint James Parish. It’s these destinations where the state’s rare historic memories keep panting against a hot Caribbean climate.

It starts with an ecological wonderland and the locals who mastered it. Who were the Cajuns? They weren’t, as most outsiders think, the unique collective French, Spanish and African descendants who built the crumbling romanticism of the Vieux Carre. Those were Louisiana’s other nonpareil ethnic group, the Creoles. No, the Cajuns were a backwoods linage of French-speaking refugees from Quebec and Castine who fled to the American South in the 1750s. And these men and women of the swamp class have never left. Many of the boat pilots running tours in the waterways of Jean Lafitte State Park are modern-day Cajuns. With an easy croak-drawl and self-effacing sense of humor, these guides steer travelers right up to the side of 10-foot alligators and then pull baby reptilian crawlers from ice chests to squirm on peoples’ laps.

Travelers can explore swamps from the Jefferson Parish’s town of Marrero, while continuing along the west bank of the Mississippi offers a different experience – an array of restaurants serving artistically altered takes on Cajun food. This is one blue collar corner of the South where ordering rum-flamed shrimp, caramel-glazed duck or a still cucumber martini is as simple as snapping your fingers. Bib or no bib, the plates come out steaming with spices sure to bloom in the sinuses, leaving crisp whips of flavor that go cracking on every corner of a wetted mouth.

And the music here is just as blistering.

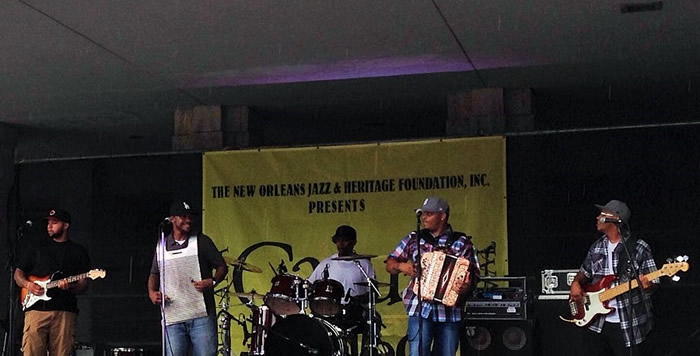

In the late 1920s New Orleans musicians began performing in corners of Jefferson Parish like Bucktown. As speakeasies began popping up, a nearly-vanished music from the rural towns found a resurgence in men like push-button accordion player Boozoo Chavis. It was Chavis – the son of a tenant farmer in Lake Charles – who helped hurl downhome Cajun-Zydeco playing back into modern world. In the coming decades Zydeco remerged from veil of the bayou and group like Chris Ardoin & NuStep established strong fan bases. During this time, Zeke’s Restaurant in Jefferson Parish held weekly Cajun Zydeco dancing lessons for the public: Its owner, Zeke Unangst, was a Hurricane Katrina evacuee who died in Texas before he return home.

When Zeke passed, the town of Metairie lost a “mischievously” beloved restaurateur who sang over the boiled crawfish and flanked himself with locals like Pee-Wee, Hambone and Rooster. It also started the path to Jefferson Parish losing its Zydeco dance floor. Yet for devotees of soul-cleansing swamp music, there was hope ahead: Boozoo Chavis’s two grandsons, R.J. and Justin, formed their own bands to keep the tradition alive: They’re now frequent flyers at the Louisiana Cajun-Zydeco Festival, New Orleans’ Jazz Fest and the annual French Quarter Festival.

R.J. Chavis and the Creole Sounds fill their speakers with the sense of hopping from cypress stump to cypress stump, ever-propelled by a drumming freight train, punchy bass flourishes and the metallic, nonstop hum of R.J.’s accordion. And this inheritor of Boozoo’s mantle can also push a carousing call through his vocals, flashing loud, aching tremors of unstoppable soul. Justin Chavis and his Doghill Stompers are equally entertaining. They bring a bluesy blister to Zydeco, fusing old time Cajun beats with heavy low-end and sharp, reeling accordion work. Put Justin Chavis and his band on a stage and see instant dancing, along with beer bottles tilting and plastic cups swirling with icy hurricanes.

West of New Orleans lays the Louisiana netherworld known as Saint James Parish. Book lovers searching for William Faulkner’s South may find it in this rural refuge of sugar cane along the Mississippi. The land is famous for its pre-Civil War era estates that lurk behind dim curtains of trees. Yet arriving at these long, timeworn entrances involves first passing highway food stops that specialize in what locals call “authentic River Road cuisine.” Among of the most famous is Nobile’s Restaurant. Nobile’s has stood on Lutcher’s Main Street for more than 122 years, a tattered, white frontier house built during the era of logging the nearby Cypress swamps. Today it flashes the comforting brilliance of River Road Cuisine with its fried oyster Po Boy sandwich, its fried chicken steak and a staple butter beans and shrimp concoction poured over fried, thin-cut fish.

At the heart of Saint James Parish is a memorable junction of elegance and brutality physically manifested in a handful of surviving plantation mansions. With architecture showcasing the heights of Greek Revival and French-Creole flourishes, these abodes are reminders of the bygone Southern aristocracy that has stayed lodged in America’s psyche from “Gone with the Wind” to “The Sound and the Fury.” Here, grand houses have grand names: The Whitney Plantation; the San Francisco Plantation; the Saint Joseph Plantation; but among these pale chateaus built on slavery, few cut deeper into the imagination than Oak Alley. Its 800-foot front walkway has been lined with 28 craning live oaks that tunnel to the house’s 28 Doric columns since the days Mississippi steam boats first stopped on the river banks in its view. Oak Alley’s current museum exhibits present a look into the lives of the sugar cane barons who owned it, as well as the enslaved residents who built its actual wealth. It also has an exhibit speaking to the land’s overall tie to the Confederate uprising. This river haven has all the curious contradictions – steeped in a chilling kind of beauty – that encapsulates the South itself. And perhaps the plantation’s best corner to contemplate it all is its tiny cemetery, during a light Louisiana rain, when the wind sweeps through the headstones and the Spanish Moss hanging from its oaks tussles in restless curtains, mimicking the eerie remembrances that make the Bayou State so hard to forget.